The Numbers Game Of Love

Can Math and Science help you find "the one"?

“It’s becoming harder for Americans to find someone to date, which means that anyone who wants to play the field should learn how to play it well.”

Our romantic relationships can often seem like the most unpredictable part of our lives. Deciding whether to go steady with someone new can be intimidating, especially when you’re unsure whether they’re truly the right person for you: there might be, as the saying goes, a lot of fish in the sea, but there’s a big difference between landing a prize catch and getting stuck with a guppy. Settle down prematurely, and you might miss your chance to meet that perfect someone; be too picky, and you may ruin your chances of finding anybody. While 47% of Americans are single, that figure mostly represents young people from 18 to 29. Outside of that range, the dating pool becomes a lot smaller. Add to that a handful of recent polls showing that it’s becoming harder for Americans to find someone to date, and it becomes easy to see that anyone who wants to play the field should learn how to play it well, and get in the game while they can.

A few key details about the average person’s dating life: the order in which most people meet their partners is so messy and complicated, it might as well be random. You also can’t usually go back to reconnect with people you’ve previously rejected, and once you’ve chosen a person to settle down with, you don’t - at least in theory continue to see other people. This can make choosing the best potential partner a very difficult task: if done at random, your chances get worse the more people you date (going out with 50 people over the course of your life, for instance, would give you a dismal 2% chance of getting it right).

This dilemma has plagued would-be romantics for decades, and its notoriety has earned it a fitting moniker, “the Marriage Problem.” In the world of mathematics, the Marriage Problem belongs to a class of scenarios encompassed by optimal stopping theory, a field of math concerned with deciding when to take a particular action in order to maximize your potential reward. Stopping theory has found use everywhere from parking-lot management to the stock market, but it applies equally well to matters of the heart.

For example, let’s say you have a rough idea of just how many people you’ll date within a given window of time. According to optimal stopping theory, you should reject the first 37% of those people. Then, pick out the person within this initial group of “rejectees” who stands out above all the rest. This person (we’ll call them “the One That Got Away”) will serve as the bar against which you judge all your dates going forward. To maximize your probability of finding the ideal match, reject everyone that you rate worse than the One That Got Away, then settle down with the first person who is just as good–or better–than them.

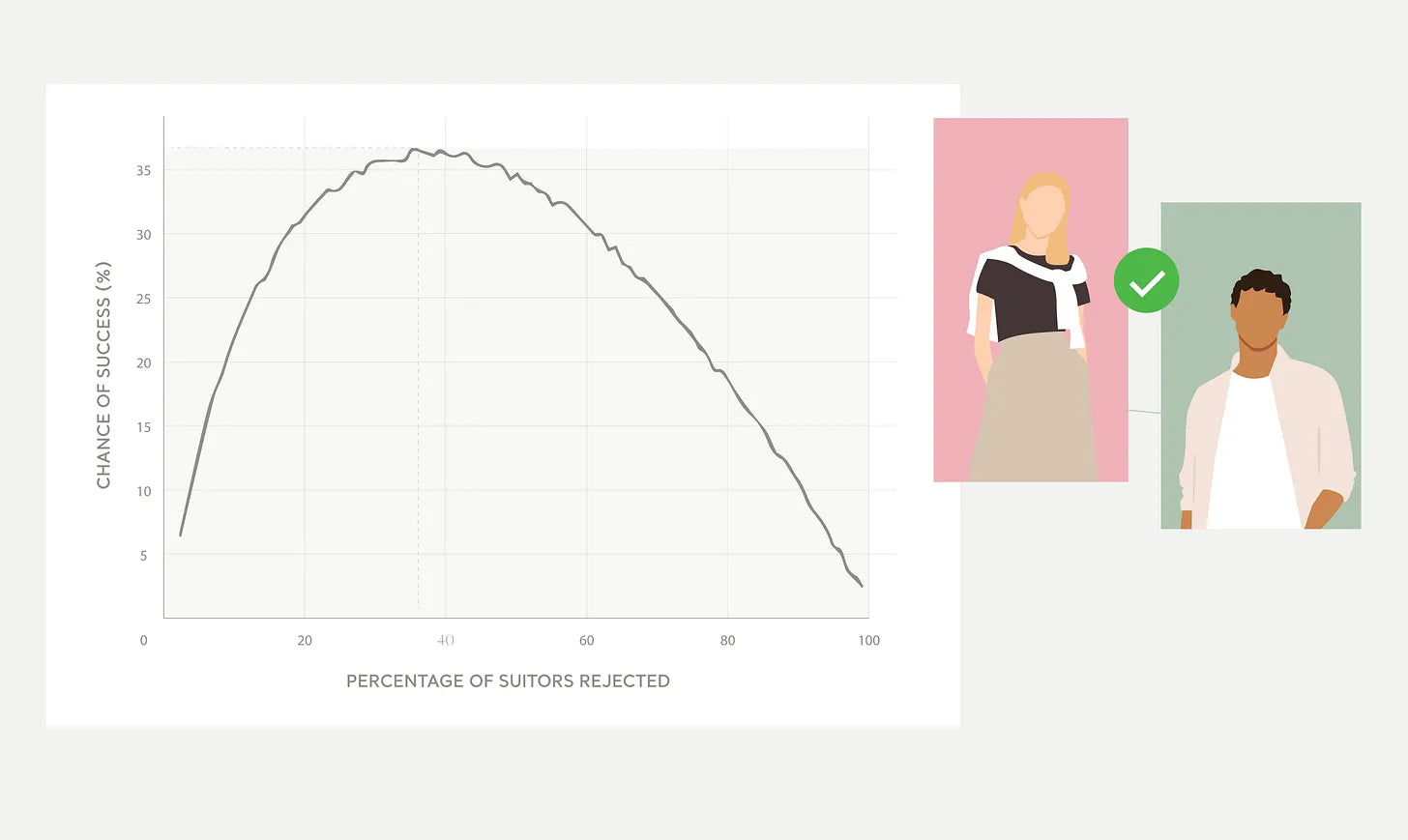

By organizing your love life this way, you place the odds strongly in your favor: whereas choosing randomly from a group of 100 people would only net you a measly 1% odds of finding a match, the strategy described above bumps those odds up to 37%; not as good as a lucky coin toss, admittedly, but much better than before, and with the added bonus that your chances only improve as the number of dates you go on increases.

This advice might sound a little harsh, and maybe a tad robotic, but it’s rooted in common sense. If you think you’re likely to enter, say, ten serious relationships over the course of your life, you probably shouldn’t settle down with the first person you meet! In fact, you probably shouldn’t settle down with the second person, either. The sweet spot, where we reject just the right number of people to zero in on our perfect person, turns out to be about 37% of our overall dating pool. When this strategy is simulated on a computer, you end up with a graph like this:

“The One That Got Away’ can serve as the bar against which you judge everyone that comes after them.”

This method obviously has its drawbacks. It’s impossible, for instance, to know exactly how many people you’ll date over the course of your life. Worse, it’s possible that, during your rejection phase, you meet somebody who would be perfect for you in every way, and who you would be forced, by the cold calculations of math, to turn down. In this scenario, the One That Got Away is your best match; it’s an unavoidable risk, and one that’s deeply present if your dating pool is small. On the flip side, it might be that the One That Got Away wasn’t so great to begin with, and has set your standards for a good relationship so low that you settle for a subpar sweetheart. In real life, however, this doesn’t have to be the case.

Perhaps this is best illustrated by one mathematician for whom the marriage problem was hardly an abstract exercise in noodling around with numbers: Johannes Kepler, the famously neurotic astronomer, developed a modified version of the marriage problem during his search for a second wife. After having courted eleven candidates over the course of several years, and using his previous marriage to help compare potential brides-to-be, Kepler worked out mathematically that the fifth candidate, a woman named Susanna Reuttinger, would be his ideal match. And as it turned out, this approach was a resounding success: though his marriage to his first wife was often plagued by bouts of unhappiness, his second marriage proved to be a very happy union.

Despite all this, it’s undeniable that romantic love is a very tricky business. A handful of formulas won’t remove the uncertainties and anxieties that come with trying to find your soulmate. But in the game of love, it’s in your interest to consider many different perspectives, whether that be through introspection, exploration, or, occasionally, dabbling in math. It’s certainly comforting to know that mathematics provides a rulebook to help you move your pieces on the board; ultimately, though, how you choose to move is up to you.